Britain is still aiding the crimes of the Zionist movement.

Bloody Balfour from Ireland to Palestine

By David Cronin December 18, 2025Editor’s Note: This article by Irish journalist David Cronin traces the origins and connections of the Balfour Declaration with Lord Balfour to Ireland and to the British occupation of Palestine until the 1940s and beyond to the current genocide.

Dating from 1890, it offers a reminder that hunger was an acute problem for a large part of the 19th century. The bellies of the Irish did not magically become full once the period in the 1840s generally referred to as the Great Famine petered out.

Image: Irish Famine Exhibition

Food shortages were still occurring while Arthur James Balfour was Britain’s chief secretary – the top colonial administrator – for Ireland, a post he held from 1887 until 1891.

Although the [golf] cartoon is potent, it does not give a complete picture. It would be a misunderstanding of history to merely denounce Balfour for engaging in leisure pursuits as the people over whom he ruled were ground down by poverty.

Balfour did not simply look the other way. Instead, he authorized extreme brutality against anyone who challenged the established order.

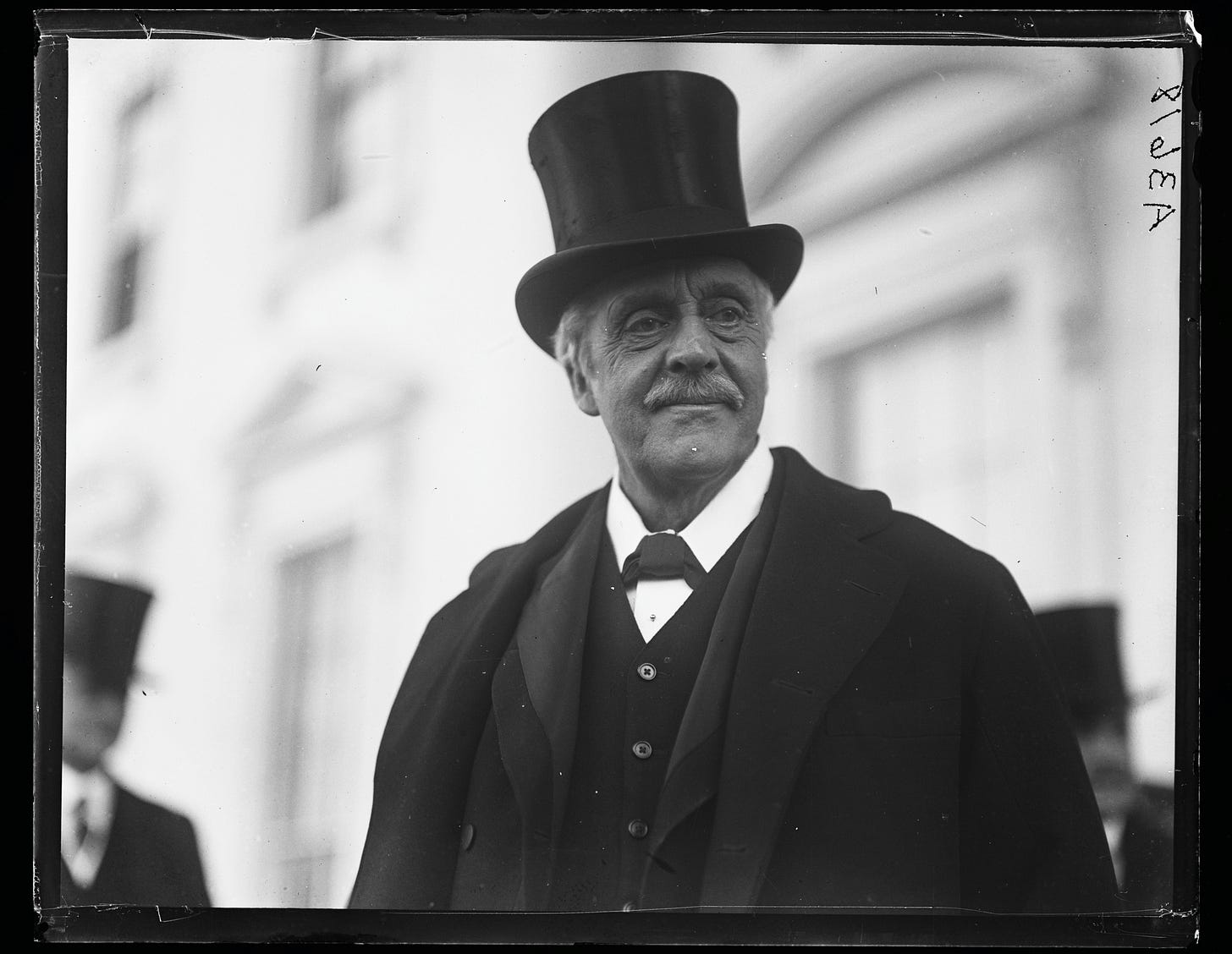

Born in the Scottish village of Whittingehame, Balfour hailed from an aristocratic background. Like so many other British supremacists, he was a graduate of Eton and Cambridge.

Given his highly privileged upbringing, nobody should be surprised to learn that he had little sympathy for Ireland’s “excitable peasantry” – as he called them.

During his first speech in the British Parliament after his appointment as chief secretary, Balfour unveiled legislation known as the Irish Crimes Act.

Under it, farmworkers who defied the landed gentry faced six months of imprisonment with hard labor.

The nickname Bloody Balfour was earned early during Balfour’s stint in Ireland. Balfour earned it because he praised police officers who opened fire on an 1887 protest in Mitchelstown, County Cork, killing three people.

The protest had been called in support of William O’Brien, a politician and agitator. O’Brien led a campaign encouraging tenant farmers to withhold payments from landlords who would not reduce rents.

Bloody Balfour had admirers, as well as enemies.

Among his biggest fans was Edward Carson, a politician still revered by many who want to preserve the so-called “union” between Britain and the north of Ireland.

As a lawyer, Edward Carson played a major part in the prosecution of William O’Brien. Carson was in Mitchelstown on the day the 1887 massacre took place and fully endorsed Balfour’s response to it.

According to Carson, Balfour “simply backs his own people up” and “there wasn’t an official in Ireland who didn’t worship the ground he walked on.”

Bigotry

Following his time as chief secretary, Balfour opposed “home rule” for Ireland when the issue was debated in the British Parliament during the 1890s. Balfour availed of one such debate to display crude anti-Irish bigotry.

He said, “The fact is that before English power went to Ireland, Ireland was a collection of tribes waging constant and internecine warfare, without law, without civilization. Although the law is imperfectly obeyed, and although civilization may be imperfectly apprehended, all the law and all the civilization in Ireland is the work of England.”

While Balfour regarded the Irish – particularly Catholics – as inferior, he packaged his brand of unionism as progressive. In a highly condescending manner, he even tried to claim the Irish as kinfolk. In 1910, The Times newspaper quoted him as saying, “While I admit differences of degree, I will never admit that the Irishman is one race of inhabitants and England or Scotland or Wales is another race.”

Despite his professed devotion to law and order, Balfour sided with loyalists in the north of Ireland who engaged in illegal weapons smuggling. Insurrection could be required, he felt, if the government in London made too many concessions to Irish nationalists.

After serving as a Conservative prime minister from 1902 to 1905, Balfour was alarmed by the Liberal government that held power for the next 10 years. He went so far as to insinuate that the Liberals’ moves towards facilitating devolution for Ireland were treasonous.

“Ordinary canons of conduct necessarily become open to question in extreme cases,” he argued in 1912. The Liberals’ “whole treatment of the home rule question,” he added, would “justify any action which the Ulster loyalists may take to maintain their rights.”

He would soon modify his hostility toward granting a certain amount of autonomy to Ireland. For reasons of realpolitik, Balfour accepted that devolution could take place, provided that it wouldn’t apply to several northeastern counties.

For unionists, “the least calamitous of all the calamitous policies” was to exclude Ulster from home rule, Balfour contended in 1913.

In April 1914, a large quantity of rifles and ammunition was smuggled into three northern Irish ports for potential use by the Ulster Volunteer Force. Balfour sought to justify the Larne gun-running operation, as it became known, by arguing that loyalists found themselves in extraordinary circumstances “of a kind which could only occur in two or three centuries without shattering the whole fabric of society.”

The weapons smuggling was regarded as so serious that it was condemned by such pillars of the British establishment as Winston Churchill.

Intriguingly, Balfour tweaked a slogan associated with Winston’s father Randolph Churchill while speaking in Parliament. The slogan that Randolph Churchill helped to popularize is “Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right.”

Balfour said in 1914, “I hold now, and I held 30 years ago, that if home rule was forced upon Ulster, Ulster would fight and Ulster would be right.”

Balfour was first lord of the admiralty – the navy’s political master – for a few years during the First World War. He held that post when Ireland’s Easter Rising broke out in April 1916.

In written comments on the rebellion a few weeks later, Balfour alleged that it had “disgraced Dublin.” He noted that many of the rising’s leaders had already been executed and insisted that the sentences decided on for other rebels would be “fully carried out.”

Balfour advocated what he regarded as a pragmatic approach in the British cabinet discussions on addressing the consequences of the Easter Rising.

Once a hardcore opponent of home rule, he now viewed it as preferable to full independence. He would, however, continue to demand that Ulster – or a large chunk of that province – be treated differently.

Visiting New York in the spring of 1917, Balfour met a number of Irish Americans who were deemed as influential. Based on those conversations, he argued that “settling” the Irish question would “no doubt greatly facilitate the vigorous and lasting cooperation of the United States government in the war.”

Imperialist

Similar thinking lay behind the most infamous document to which Arthur Balfour attached his name. I am referring, of course, to the Balfour Declaration of November 1917.

That pledge to support the establishment of a “national home” for the Jewish people in Palestine clearly did not result from any altruistic motives.

Rather, it reflected the belief that currying favor with Jews in Russia and the US would be advantageous to Britain at a time when there were real fears it could lose the First World War.

Balfour put forward the case that most Jews in Russia and America had a positive view of Zionism. A statement that endorsed Zionist aspirations should allow Britain to conduct “extremely useful propaganda” in both those countries, Balfour claimed.

The case made by Balfour was guided by hearsay rather than evidence.

Far from being a powerful homogenous bloc, Jews in Russia were victims of persecution. Balfour’s Foreign Office ignored a report from the British ambassador in Petrograd stating that Russian Jews did not have the clout to alter the course of the war.

The wording of the Balfour Declaration was ambiguous. Subsequent comments by Balfour nonetheless leave no doubt that he was backing a colonization project under which European settlers would be accorded a much higher status than Palestine’s indigenous people.

In 1919, Balfour wrote, “We are dealing not with the wishes of an existing community but are consciously seeking to reconstitute a new community and definitely building for a Jewish majority in the future.”

He also put forward the theory that Zionism was rooted in traditions, needs and hopes “of far profounder import” than the “desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.”

The Balfour Declaration is an imperialist document.

Chaim Weizmann, the representative of the Zionist movement who was most involved in the talks which led to the declaration, presented himself as an Anglophile. Befriending the “Jews of the world,” would, in Weizmann’s words, be something that “matters a great deal, even for a mighty empire like the British.”

The British Army was not charmed by Zionists in the way that leading politicians were.

Not long after the Balfour Declaration was issued in 1917, British troops wrested control of Palestine from Turkey.

Edmund Allenby, the general commanding the British troops, banned all mention of the declaration. Allenby’s decree appears to have been sparked by worries that Arabs would resist if Britain’s backing for the Zionist colonization project was publicized.

Within a few years, the Balfour Declaration had gone from being a simple letter to something that was being actively implemented. Its core objective – building a Jewish “national home” – was enshrined in the League of Nations’ mandate under which Britain would rule Palestine from the 1920s to the 1940s.

In her book, The Hidden History of the Balfour Declaration, Sahar Huneidi identifies Herbert Samuel, Britain’s first high commissioner in Palestine, as being central to making Zionist aspirations a reality.

Herbert Samuel was a committed Zionist who had played a significant part in the lobbying which led to the Balfour Declaration. “Samuel’s extreme Zionist interpretation of the Balfour Declaration,” Sahar Huneidi writes, “tipped the scale towards the Zionists, at a time when the Balfour Declaration itself was considered an experiment, the results of which were to be determined with the passage of time.”

The “experiment” made an impact. Through a series of ordinances, Herbert Samuel helped Zionist settlers to buy up land and evict Palestinian farmers en masse.

“Second Ireland”

The consequence of the “experiment” was that Britain transformed Palestine into a “second Ireland.” That was the verdict of the newspaper tycoon Alfred Harmsworth, also known as Lord Northcliffe, who paid a visit to Palestine in 1922.

Harmsworth’s observation was perceptive. Britain’s rulers sought to crush resistance in Palestine using comparable means and often the same individuals they had inflicted on Ireland.

Perhaps the most telling illustration of that fact is that Winston Churchill, Britain’s colonial secretary during the early 1920s, assembled a militarized police force to deal with those Palestinians who weren’t sufficiently obedient for his liking. The force consisted of men from the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries.

To this day, the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries remain despised in Ireland. Their contribution to the country’s War of Independence involved shooting dead numerous civilians and burning down houses, pubs and factories.

Arthur Balfour kept on praising the declaration bearing his name for its “wisdom,” as he put it in 1927.

Balfour died three years later. The effects of the Balfour Declaration endured.

Caroline Elkins pinpoints those effects in her book Legacy of Violence.

She writes about how by the 1930s Palestine “replaced Ireland as the official and unofficial training ground for colonial police indoctrination, and it produced scores of senior police officers and future paramilitary counterinsurgents for the entire empire.”

The “skills” acquired through such training were put to use when a major revolt took place in Palestine between 1936 and 1939.

Britain’s crushing of that revolt involved immense cruelty. Torture against detainees was approved at a high level; the thousands of people killed by the British included patients in hospital beds; and Jaffa’s Old City was largely destroyed, causing mass homelessness.

The repression of the revolt was among Britain’s worst crimes during the twentieth century, though knowledge about this shameful period is woefully inadequate in present-day Britain. Hopefully, the success of Annemarie Jacir’s new movie Palestine 36 will alert the general public to facts that the British elite would happily erase from history.

Britain did not just train its own officers in Palestine. It trained the Zionist militia known as the Haganah, too.

The Haganah was the main force responsible for expelling up to 800,000 Palestinians from their homes between 1947 and 1949. We should never forget, therefore, that a large proportion of the men who perpetrated the Nakba had been mentored by Britain.

Impudence

Nakba means catastrophe in Arabic.

The catastrophe inflicted on Palestine in the 1940s never ended. Its consequences are being exacerbated by a genocide in the 2020s – a genocide that has not ended either.

The British government – then led by Rishi Sunak – backed the genocide with considerable enthusiasm as it got underway in 2023.

Sunak’s successor Keir Starmer has maintained the appalling situation whereby RAF reconnaissance flights taking off from and landing in Cyprus provide so-called “intelligence” to the Israeli military invaders of Gaza.

Matt Kennard, a journalist who has meticulously monitored these flights, is 100 per cent correct in pointing out that they make Britain a participant in genocide.

Rather than being held to account for taking part in the worst possible crime, Britain’s rulers have proscribed Palestine Action.

The proscription shows the absolute contempt in which the establishment holds ordinary people, particularly those with the courage to try and disrupt violations of international law.

Six ordinary people who have been imprisoned for opposing genocide are on hunger strike at this very moment.

Just this week, we witnessed the sordid spectacle of elected representatives laughing in Westminster when a question about the hunger strikers was raised.

Earlier, I referred to an 1890 political cartoon captioned “Ireland wrestles with famine, while Mr. Balfour plays golf.”

In December 2025, Gaza is still wrestling with starvation despite a so-called ceasefire. Six brave people in British jails are refusing food to protest against how they are being punished for opposing a genocide.

The genocide has been aided by the British ruling elite. Rather than expressing any remorse for what they have done, members of the elite have the impudence to laugh.

•This talk was given during a webinar organized by the Scottish Palestine Solidarity Campaign.

Rise Up Times is entirely reader supported.

In this critical time hearing the voices of truth is all the more important although censorship and attacks on truth-tellers are common. Support WingsofChange.me as we bring you important articles and journalism beyond the mainstream corporate media on the Wings of Change website and Rise Up Times on social media Access is alway free, but if you would like to help:

A donation of $25 or whatever you can donate will bring you articles and opinions from independent websites, writers, and journalists as well as a blog with the opinions and creative contributions by myself and others.

Sue Ann Martinson, Editor ![]()

Whatever you are able donate will bring you articles and opinions from independent websites, writers, and journalists as well as a blog with the opinions and creative contributions.

Whatever you are able donate will bring you articles and opinions from independent websites, writers, and journalists as well as a blog with the opinions and creative contributions.